A Day (Or Two) In the Life of a Commercial Landlord and Tenant Litigator – CLE for the NYSBA Commercial Leasing Committee

November 1, 2017 (revised July 24, 2022)

On November 30, 2017, Michelle Itkowitz was honored to teach a continuing legal education class to the New York State Bar Association, Real Property Section, Commercial Leasing Committee. The presentation was entitled:

Here is a link to the full materials. Here is an excerpt from the materials:

I. INTRODUCTION TO THIS PRESENTATION

You are done drafting that commercial lease. Maybe you represented the landlord. Maybe you represented the tenant. Your client was happy. You got paid. Both parties went away with enthusiasm for the future, at the threshold of a new chapter for their businesses and the physical space. You close the file.

But what happens when there is…a default? Now your lease is put to the test.

The author of these CLE materials is a landlord and tenant litigator in the City of New York for over twenty years. I work on both commercial and residential litigations. I represent both landlords and tenants. I do NOT draft commercial leases! Alas, I am not there when the champagne is passed around on the day the lease is executed. No one thinks to call me to share in the good times. I do spend my days, however, hunched over big thick commercial leases and their riders, amendments, modifications, and attendant guarantees. People call me when things go wrong.

This continuing legal education program is designed to share with drafters how the lease clauses they construct perform in a fairly typical commercial landlord and tenant litigation, by taking the audience through an ACTUAL (and the most recent) case that came across my desk. I will present the material in the order in which I, as a litigator, am forced to think about it. We will explore:

• The description of the premises and the floor plan

• The default and remedies clauses of the lease

• The security clauses

• Additional rent

• The conditional limitations

• Service of process in a landlord and tenant proceeding

• The interplay between the lease and the guaranty

I am interested in hearing the audience’s feedback about how clauses could be set up differently and why they are drafted the way they typically are.

***

F. Conditional Limitations

Back to our lease – Paragraph 28(A)(i) makes non-payment of rent a default subject to a conditional limitation, on a 7-day notice to cure and a 5-day notice of termination.

Paragraph 28(A)(ii) makes it a defaulting under any other provision of the lease subject to a conditional limitation, on a 20-day notice to cure and a 5-day notice of termination.

One of the landlord’s most powerful remedies, a default subject to a conditional limitation pursuant to the lease, permits the landlord to terminate the lease by following certain procedures.

1. Types of Defaults Subject To Conditional Limitations in a Lease

a. Non-Rent Defaults Subject to Conditional Limitations

The following are events of default subject to a conditional limitation under a typical form of Store Lease:

“If the Tenant defaults in fulfilling any of the covenants of this lease other than the covenants for the payment of rent or additional rent; or if the demised premises becomes vacant or deserted; or if any execution or attachment shall be issued against Tenant or any of Tenant’s property whereupon the demised premises shall be taken or occupied by someone other than Tenant; or if the lease be rejected under Section 365 of Title II of the U.S. Code (Bankruptcy Code); or if Tenant shall have failed, after five (5) days written notice, to redeposit with Owner any portion of the security deposit hereunder which Owner has applied to the payment of any rent and additional rent due and payable hereunder; or if Tenant shall be in default with respect to any other lease between Owner and Tenant; or if Tenant shall fail to move into or take possession of the premises within thirty (30) days after the commencement of the term of this lease….”

Other defaults which may be included in the lease as subject to a conditional limitation are:

• assigning, mortgaging or encumbering the lease or subletting without the landlord’s permission

• the filing of a mechanic’s lien against the premises which is not discharged within a period of time after notification of the tenant by the landlord

• the failure to maintain insurance

• assigning the lease, or any interest in the lease, transfer ownership of the lease

• illegal sublets

• closing for a period of ten or more days not for landlord authorized renovations

b. Nonpayment of Rent as a Conditional Limitation

Although the many leases specifically exclude such, a lease can provide a mechanism whereby the landlord may terminate the lease, after default in the payment of rent, in the commercial context. Properly drafted, a conditional limitation clause for the nonpayment of rent in a commercial lease will be enforced by the courts and is, perhaps, the landlord’s most powerful remedy, nonpayment being the most common default. This is particularly true where the market has quickly improved and the lease-rent has fallen “below market.” A properly structured conditional limitation for the non-payment of rent should utilize the language cited approvingly by the court in Grand Liberte Co-op Inc. v. Billhaud,[fn1] expressly making the conditional limitation applicable to rent defaults and stating that “it [is] the intention of the parties hereto to create hereby a conditional limitation.”[fn1]

Note, however, that this strategy will not work in a residential context. A conditional limitation regarding the nonpayment of rent in a residential lease has been held to violate public policy as it would provoke a forfeiture, and the law disfavors automatic forfeitures of residential tenancies.[fn2]

2. Notice to Cure

In many commercial leases, the landlord must first notify the tenant of the default and set forth a time period in which the tenant must cure the default; or, if it is impossible to cure within the time period, it must set forth a time period in which the tenant must begin curing the default. The time period in many commercial leases is fifteen (15) days. This notice is commonly referred to as a “notice to cure” or “notice of default.”

3. “Yellowstone” and Tolling Time to Cure Defaults

Giving a notice to cure may force the commercial tenant to initiate a proceeding in Supreme Court commonly referred to as a “Yellowstone,” so called after the case of First National Stores v. Yellowstone Shopping Center.[fn3] The essence of a Yellowstone proceeding is a declaratory judgment complaint accompanied by a stay application (which is routinely granted, at least in the form of a temporary restraining order, pending a hearing on a preliminary injunction), which seeks a trial on the issue of whether the tenant is indeed in violation of the lease. This procedure is designed to toll the time the tenant would ordinarily have to cure a lease violation while the court resolves the issue of whether the tenant is indeed in violation and/or has cured the violation. If the court finds the tenant in violation, then by virtue of the stay of the notice to cure, the tenant still has the opportunity to cure the violation before the cure period ends. This process in itself can buy the tenant significant time as the resolution of the proceeding can take months, if not years.

The purpose of a Yellowstone injunction is to maintain the status quo by means of a temporary stay while the tenant challenges the landlord’s notice to cure.[fn4] Thus, the Yellowstone injunction tolls the cure period set forth in the landlord’s notice of default until there is a judicial determination of the parties’ rights.[fn5]

To demonstrate one’s entitlement to a Yellowstone injunction, a tenant must demonstrate that he/she: (i) holds a valuable commercial lease (ii) has received a notice to cure; (iii) has requested injunctive relief prior to the termination of the lease; and (iv) is prepared and maintains the ability to cure the alleged default by any means short of vacating the premises.[fn6] “These standards reflect and reinforce the limited purpose of a Yellowstone injunction: to stop the running of the applicable cure period.”[fn7]

A Yellowstone injunction can provide a modicum of protection to landlords as well as tenants, because they are often conditioned upon the tenant’s ongoing payment of rent and/or the posting of a bond to protect the landlord from a wrongfully issued injunction.

The First Department has held that commercial tenants have a right to a virtually automatic issuance of a Yellowstone injunction[fn8] and has held that in order to obtain a Yellowstone, rather than requiring the tenant to prove on his application that he can cure the alleged default, a tenant must merely state his desire and ability to cure the default by any means short of vacating the premises.[fn8] Furthermore, a tenant is entitled to a Yellowstone injunction when the tenant argues that he is not in violation of the lease, and that if he is, he concedes to cure any such violations.[fn9]

If the tenant is successful in having the Yellowstone injunction implemented, then the landlord must answer the Supreme Court action and counterclaim for termination of the tenancy. This is an example of a landlord and tenant dispute in a summary proceeding being litigated in a forum other than civil court.

An invariable condition of a Yellowstone Injunction is that the tenant is ordered to pay rent during the pendency of the action.

4. Termination Notice

If no Yellowstone proceeding is commenced and the default is not cured or being cured by the date specified in the notice to cure or if the default is not curable (see below), then the landlord may notify the tenant that the lease will be terminated in a certain number of days. In such case, many commercial leases allow termination in five (5) days. This notice is commonly referred to as a “notice to terminate.” After the expiration of the termination notice, the landlord may commence a summary holdover proceeding against the tenant to recover possession of the premises.

Notices to cure and notices to terminate pursuant to the terms of a lease are served on the tenant in accordance with the lease. No statute specifies other methods of service for notices given strictly pursuant to a lease.[fn10] If the lease is silent on a method of service, the method used must be “reasonable.”

***

6. Defaults the Tenant Refuses To Cure

If a tenant’s position is that it refuses to cure the default, Tenant can’t have the Yellowstone. In Linmont Realty, Inc. v. Vitocarl, Inc., 147 A.D.2d 618 (2nd Dept. 1989), the Yellowstone application was denied. There were 17 defaults, including failure to renew environmental liability insurance, failure to keep daily records of gasoline inventory, failure to have tanks tested, failure to permit the defendants to inspect records of tank tests and inventory control, failure to clean and maintain the premises, and illegally subletting a portion of the premises for the storage and distribution of newspapers. The Linmont court reasoned:

To procure a Yellowstone injunction, a commercial tenant must demonstrate, inter alia, that it has the desire and ability to cure the alleged default by any means short of vacating the premises. The plaintiff herein has made no offer to cure any of the charged defaults, alleging instead that many of the alleged defaults listed in the Notice of Termination of Lease were not its responsibility, that various conditions did not exist as claimed by the defendants, and that the remainder of the defaults had been waived by the defendants acceptance of rent with knowledge of their existence. [(internal quotation marks and citation omitted)].

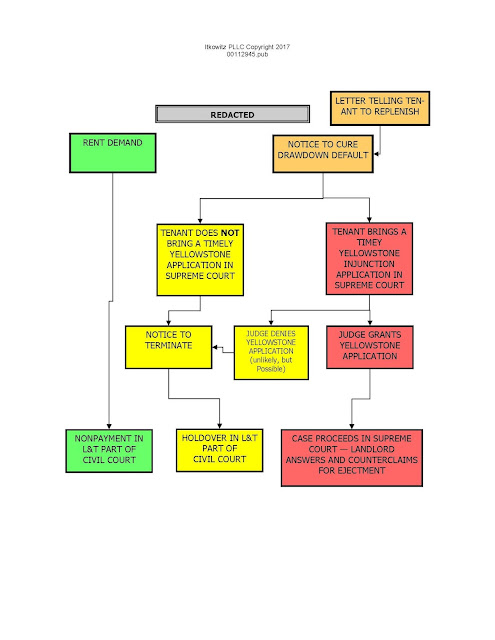

[Finally, here is a chart from later in the presentation:]