Feuding Co-Op Owners: What Is A Board To Do?

October 29, 2013

On October 29, 2013 Jay B. Itkowitz spoke at the Douglas Elliman Property Management Team and his talk was entitled: Feuding Co-Op Owners What Is A Board To Do?

Below is a reprint of most of the materials that accompanied the talk.

By Michelle Maratto Itkowitz and Jay B. Itkowitz; Copyright Michelle Maratto Itkowitz 2013 Itkowitz PLLC.

Feuding Owner’s — What’s A Board To Do?

I. INTRO

Here’s a hard truth — Co-op boards are filled with people who want power, but who are often not comfortable exercising the responsibility that goes with it.

People join their co-op boards because they want to protect their investment and their home, and they want control of what goes on in their building. That is noble. With a board position, however, comes power. And as the old saying goes, with power comes responsibility.

In our practice, we see all too often what happens when people in positions of power on co-op boards refuse to take responsibility and make hard choices about what is going on in their building.

Unfortunately, the failure to act when faced with a problem in the co-op will frequently end up costing the co-op more money, time and hassle in the end.

In these materials, we talk about the rights and responsibilities that shareholders have to each other and how boards can mitigate costly, expensive and time-consuming litigation.

II. SOME CASE STUDIES – WHAT TO DO WHEN THE STUFF HITS THE FAN (LITERALLY)

In this section we offer you two actual case studies. One where the board and the managing agent sat back and did nothing in the face of a very bad situation and ended up paying the consequences for their inaction. The other where the board and the managing agent took action and solved a problem.

A. RAW SEWAGE LEAKING DOWN FROM ONE UNIT TO THE OTHER IN A NICE MANHATTAN CO-OP

We recently represented a shareholder in a fancy Manhattan co-op who was forced to take legal action in her co-op because the board completely refused to deal with its obligations to her and other shareholders.

No less than seven times in a three-month period, water containing raw sewage and human feces leaked into our client’s apartment from the unit above. These floods were extremely damaging to the client’s health, as well as to the apartment itself. The water poured into our client’s kitchen, dining room and library through the ceiling and light fixtures. These floods rendered the apartment unusable, as the flood waters were unduly malodorous and shorted out the electrical system.

The floods occurred because the occupant of the unit one floor over our client’s unit, the mother of the shareholder, was living alone and had become mentally impaired. She was stopping up the toilet with cigarette butts. This was well documented by the building’s superintendent crew.

Our client, obviously, repeatedly complained in writing and otherwise to the managing agent (not Douglas Elliman) and the board.

In response to the early floods, the board and the managing agent sent disaster crews to the apartment to clean and disinfect and to remediate the damage to the apartment. Then, after the third flood, the board and the managing agent simply refused to make the necessary repairs, citing no reason. Neither did the board or the managing agent do anything to attempt to help the obviously ailing shareholder in the apartment causing the floods.

Our client asked for an abatement of maintenance, and her request was refused.

Ultimately, we were forced to sue the upstairs shareholder, the occupant, the board and the managing agent and move for a temporary injunction – which was granted. Insurance companies got involved. There was lengthy discovery (exchange of documents).

In the meantime, on a slow news day, a New York City paper picked up the story from the courthouse, and that managing agent and building were (one would assume) extremely embarrassed by the story.

The case settled before depositions began, with the co-op paying our client for her trouble.

Bottom line, would you like this headline to be in the New York Post about a building you were managing? And this is the literal headline and first few lines of the story:

This story refers to a “condo”, but the unit was a co-op. That’s the press for you.

B. OLDER LADY SHAREHOLDER WALKING WITH BATHROBE OPEN (AND NOTHING ON UNDERNEATH) AT EXPENSIVE CO-OP BUILDING’S POOL

We also had a case where an aging professional woman in her sixties was making her fellow shareholders uncomfortable by walking around the coop swimming pool with an open bathrobe. The problem was under the bathrobe was no bathing suit or any other clothing. Fellow shareholders did not appreciate being subjected to the unasked for exhibition, which occurred on a regular basis. At the same time, the woman, who was not in possession of all her previous faculties, was falling behind on her maintenance.

So the Board acted by commencing a nonpayment of maintenance case, on which she defaulted, and ultimately, after protective services was called, she was evicted. Her sons became involved and relocated the woman to a more appropriate environment. Ultimately, the woman’s proprietary lease and shares were sold at a marshal’s auction to a more desirable family.

C. COMPARE THE COST OF DOING NOTHING WITH THE COST OF TAKING CARE OF BUSINESS

1. The Cost of Doing Nothing

In the first example above, with the sewage leak, the cost to the board and the managing agent of doing nothing was:

• Bad press.

• Higher legal fees.

• Forced to pay a settlement to the shareholder.

• Their insurance company was involved in their defense – higher premiums upon renewal?

• Time and energy of board members and managing agent staff.

2. The Benefit of Doing Something in a Timely and Responsible Way

• Discretion in a delicate situation.

• Lower legal fees.

• Problem was resolved with the sale of the unit to a more desirable shareholder.

• Tenants could feel like the board and the managing agent cared about the residents of the building.

III. ANATOMY OF A NUISANCE OR NONPAYMENT CASE AGAINST A SHAREHOLDER – WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENS

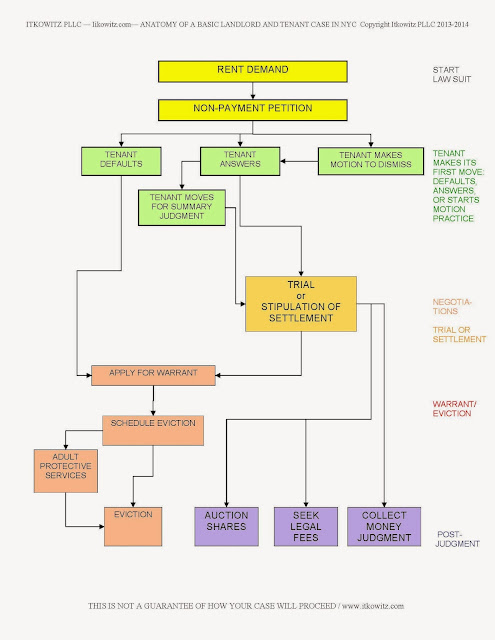

In this section we demonstrate how a case against a shareholder typically proceeds, first in the nonpayment of maintenance context and then in the nuisance context.

A. NONPAYMENT

• Predicate Notices

• Nonpayment Summary Proceeding

• Default or Trial

• Marshal

• Auction Shares

• Nonpayment Summary Proceeding

• Default or Trial

• Marshal

• Auction Shares

B. NUISANCE LAWSUIT

• Predicate Notices

• Summary Proceeding OR Regular Supreme Court Law Suit

• Default or Trial

• Marshal

• Auction Shares

• Summary Proceeding OR Regular Supreme Court Law Suit

• Default or Trial

• Marshal

• Auction Shares

SEE THE BELOW FLOW CHART

IV. SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS

A. ACT FAST

Encourage your board to deal with difficult issues head on. This does NOT mean necessarily to act quickly or impulsively. But at the very least, a board should always be seeking to educate itself.

In our practice, we provide clients with a Legal Project Management Letter whenever they are faced with a decision or a difficult situation. Each Legal Project Management Letter includes a section on:

(1) The Facts. A review of the facts and a synthesis of the “hard” data (such as dates and names, contract provisions, summaries of substantive emails, etc.) with the “soft” information, like the subtleties of board politics.

(2) The Law. A survey of the law relevant to the case, so that everyone understands the shareholders’ and the board’s rights and responsibilities.

(3) The Goals. A clear restatement of the client’s goals, so that we can be sure that the client and the firm have an identical understanding of what success looks like for the board.

(4) The Options. A presentation of available options. For each option, we provide:

(a) Pros.

(b) Cons.

(c) Time.

(d) Cost.

(e) Risks.

(f) Percentage chance of the option advancing the goals.

(b) Cons.

(c) Time.

(d) Cost.

(e) Risks.

(f) Percentage chance of the option advancing the goals.

(5) The Money. A frank discussion about the budgetary constraints and of legal fees, and suggestions for fee arrangements that are alternatives to hourly billing.

(6) A Communications Plan. We establish a communications plan. Especially if there are many people involved in the case at the firm, on the board, at the managing agent, etc.

(7) A Recommendation. A recommendation for a course of action.

B. OTHER SUGGETSIONS

Educate yourself boards about the cost of sitting on problems and the legal process. Also, have emergency contact information for all shareholders, in case a shareholder living alone needs assistance.