How NYC Landlord and Tenant Law Affects Value — What Appraisers Must Know

May 29, 2014

On May 19, 2014 Michelle Maratto Itkowitz and Jay B. Itkowitz presented a certified Appraisers Continuing Education Program to the Columbia Society of Real Estate Appraisers. The title of the 3 hour presentation was: “How NYC Landlord and Tenant Law Affects Value — What Appraisers Must Know”. The presentation was so popular that Michelle and Jay have been invited back for September 2014. A copy of the first chapter of the materials is reprinted below (without footnotes).

I. INTRODUCTION

The old saying goes that the three most important things about real estate are (1) location, (2) location, and (3) location. We get that, and, of course, the Upper East Side of Manhattan is pricier than Mill Basin Brooklyn. Keeping that rule in mind, one should add our rule about the three other most important things about multi-family real estate, and they are: (1) the tenancies, (2) the tenancies, and (3) the tenancies. To us as litigators who work extensively in the landlord and tenant law space in New York City, a building’s value is a function of the tenancies. Is a building really just an address; is a building really just bricks and mortar? Does the address or the structure have any independent value without the tenancies – without the people who pay the rent?

Landlord and Tenant Law (especially that surrounding Rent Stabilization) can have a profound effect on the value of multi-family buildings in New York City and State. And it continues to surprise us how misunderstood Rent Stabilization is by owners, managers, and…yes…appraisers.

A. GOALS OF THIS SEMINAR

Since we began drafting these materials in 2000, we have been noting the annual number of summary proceedings filed to recover rent and/or possession of real property in New York City. Those numbers are contained in the chart below. The New York courts are open for approximately 250 days a year. Therefore, in an average year, 1307 new proceedings are filed each day that the courts are open for business. In other words, there is a huge volume of eviction cases working its way through the court system.

We live in a city. And in a city people are crowded closely together, and they are competing for scarce resources, such as housing and places to run their businesses. That’s truer than ever as the population of NYC rises. Hopefully, most of that competition plays itself out in the courts, thus 1,307 new landlord and tenant cases per day.

This size caseload produces interesting jurisprudence, there are many subtleties, there are many conflicts between different appellate departments, appellate terms, and even judges in the same borough. This is a very politicized area of law. It’s also very business-oriented, very market-sensitive. As an L&T lawyer you are busy in a good market or a bad one. In a good market landlord’s want to get out tenants with under-market rents. In a bad market landlord’s want to pressure tenants to pay.

L&T law is basically real property law, with lots of twists; the concept of private property and the ability to grant temporary estates in real property and terminate them, undergird our society and our economy. So it’s a very interesting area.

Accordingly, this series seeks explain the actual nuts and bolts of landlord and tenant law in New York City (and, to some extent, the State), and to attempt to relate that knowledge back to the concept of VALUE.

B. SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS

In most instances when a landlord finds it necessary to sue a tenant to recover rent or possession of a premises, the proper vehicle is a summary proceeding for the recovery of real property. A summary proceeding for the recovery of real property (“summary proceeding”) is an expedited lawsuit for the recovery of rent and possession of a premises created by the New York State Legislature in 1820 and governed by Article 4 of the Civil Practice Law and Rules (“CPLR”) and Article 7 of the Real Property Actions and Proceedings Law (“RPAPL”). Summary proceedings are expeditious because the parties’ procedural rights and remedies are severely limited. Among other things, for example, the tenant’s time to answer the lawsuit is accelerated and, absent leave of court, there is no discovery.

Due to the accelerated nature of a summary proceeding and the limits on pre-trial discovery, a landlord prosecuting such a proceeding is held to a higher standard with respect to complying with the technical requirements of the RPAPL. In general, even though courts have adopted more liberal standards in recent years, technical defects that might have no effect on a plenary action will mandate dismissal of a summary proceeding.

For the most part, we are not concerned in these materials with a plenary lawsuit (i.e., a regular lawsuit filed in a non-landlord and tenant part of the Civil Court of the City of New York or in the Supreme Court of the State of New York). Sometimes, however, it is possible, desirable, or even necessary, for a landlord to sue to recover rent or possession of a premises in a plenary action. We will consider these less frequent occasions later in these materials.

C. OCCUPANCY RELATIONSHIPS

Before going any further with our discussion of summary proceedings, it is helpful to briefly discuss who is in the space. A person (or a company) physically occupying a premises can give rise to many different relationships between that person and the person (or company) with paramount title to the space.

Throughout these materials we often refer to the person or company with paramount title as “landlord” and the person occupying the space as “tenant”. It is important for a clear understanding of summary proceedings, however, to note that certain summary proceeding can be utilized by anyone with paramount title (whether or not a landlord) against anyone in occupancy of a space (whether or not a tenant). Throughout these materials, when these distinctions matter, we will point them out.

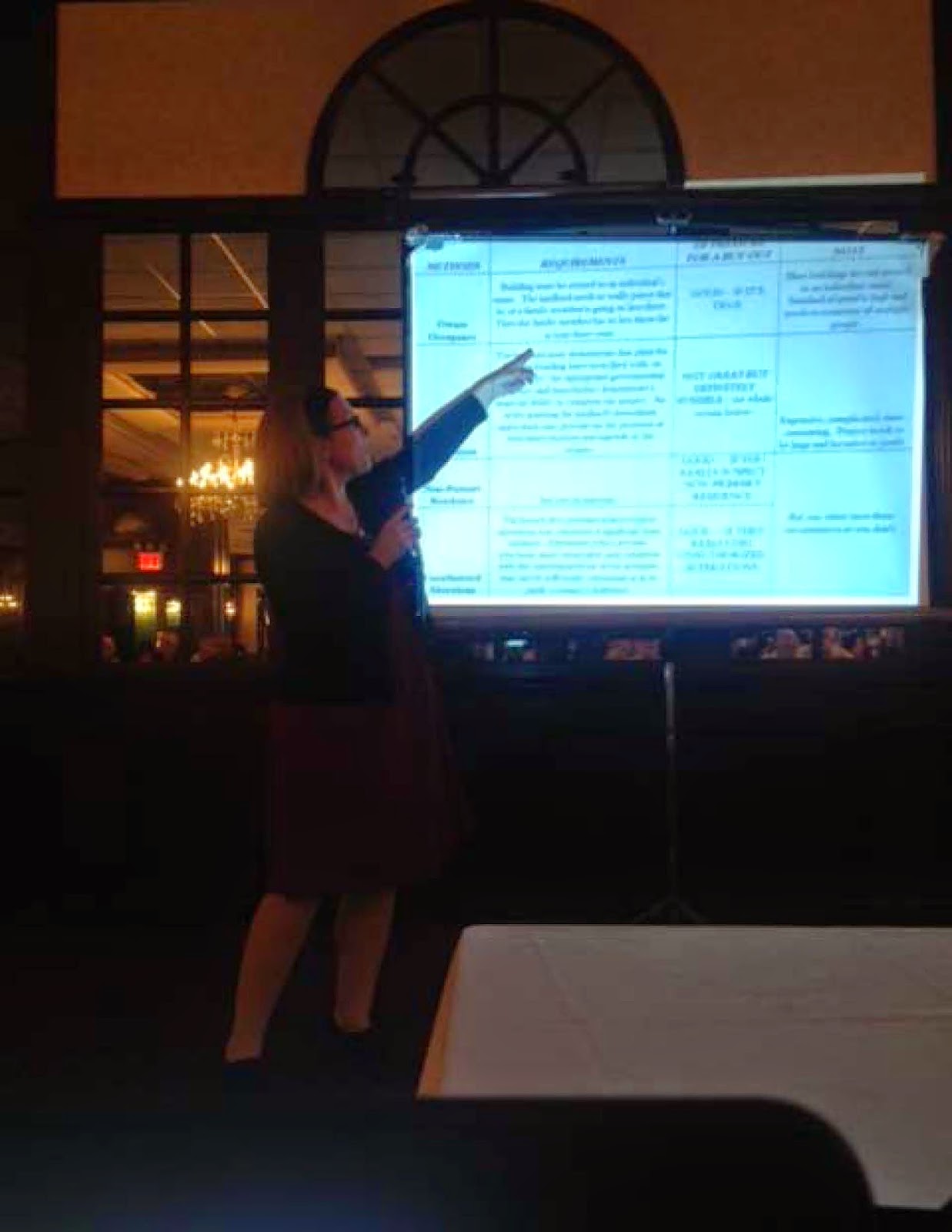

Below is a chart that describes the different statuses that a person (or company) occupying a space might have.

D. NONPAYMENT VS. HOLDOVER

There are two types of summary proceedings: nonpayment proceedings (“nonpayment”) and holdover proceedings (“holdover”). A nonpayment is a lawsuit for the recovery of rent due and, in the absence of full and timely recovery of rent due, possession of the premises. A holdover is a lawsuit for possession of the premises, regardless of the payment of rent, although past due rent or a fee for using and occupying the subject premises may also be recovered in a holdover.

The distinction between a nonpayment and a holdover, and the circumstances under which each may be initiated, are confusing to many people. The chart below demonstrates the characteristics of a nonpayment and a holdover.

Regarding a holdover, why would a person or company in a space not be entitled to be in possession of the space? The following are some examples:

*Tenant at Sufferance — Company A was a tenant. Company A let Company B, its illegal sub-tenant, into the space. Company A vacated the space. Landlord never collected any rent from Company B. Company B became a “tenant at sufferance”, Landlord suffered Company B’s presence. This is not a real tenancy, however. Company B has no right to remain in the space. Landlord gives Company B the proper predicate notice and commences a holdover.

*Tenancy Ended By its Own Terms — John was a residential tenant, but not rent regulated. John’s lease ended on June 30, 2007. John kept paying rent and Landlord kept accepting it — this made John into a month-to-month tenant — but John had no right to remain in the space. After serving the proper predicate notice, Landlord commenced a holdover.

*Tenancy Ended Because Tenant Violated Lease — Jane was a Rent Stabilized tenant. Jane moved out of her rent Stabilized apartment and illegally sub-let it for a 100% profit to someone else. This is prohibited by the Rent Stabilization Law. Landlord sent Jane the proper notices at the proper time and thereby terminated her tenancy. Then Landlord commences a holdover.

You can only bring a nonpayment when a tenant fails to pay the rent. Thus there seem to be a greater variety of situations in which you can bring a holdover. Holdovers, however, are actually commenced much less frequently then nonpayments. According to Judge Ernest Cavallo, the supervising Judge of the Landlord-Tenant Part of Civil Court in Manhattan, in 2002 there were 78,509 non-payment cases filed in Manhattan, compared with 6,600 holdovers; but Judge Cavallo said that even though holdovers only represent eight percent (8%) of the caseload, they are at least a third of the cases that go to trial.

A question often asked at this point is: “Why can you not bring a holdover for the non-payment of rent? How can failing to pay the rent on time not be a violation of a provision of the lease that would cause the lease to end early?” The answers are – in the residential context, there is a statute prohibiting as a matter of public policy any automatic forfeiture of residential tenancies for non-payment of rent, and in the commercial context most leases are drafted to prohibit forfeitures of tenancies for the non-payment of rent. In the commercial context leases sometimes allow you to bring a holdover when the tenant has an unexpired lease and he is not violating any other provision of the lease besides the covenant to pay rent. Whether or not a lease contains this provision is usually the result of market forces at the time of the lease negotiation.

If the landlord has the option of bringing either a nonpayment or a holdover, the following are some major advantages and disadvantages of each. A nonpayment usually moves faster than a holdover. If the tenant pays the rent, or is able to demonstrate why it does not owe the rent, the tenant wins the proceeding. A holdover is usually a bit more challenging to prosecute than a nonpayment and takes longer. Payment of rent, or disproving that rent is owed, is not a defense to a holdover, however, and if the proceeding is properly prosecuted, it may terminate the tenancy. Deciding which summary proceeding to institute really depends on the landlord’s goals and the lawyer’s or managing agent’s strategy. Maybe a landlord really wants a tenant out because the market is such that the landlord can rent the space for more. Suppose the lease has expired and now the tenant is a month-to-month tenant, so a thirty-day notice of termination is required as a predicate to initiating a holdover proceeding. The managing agent or lawyer, however, should ask the following questions: (1) How much rent does the tenant owe? (2) Can I prove it? and (3) If I can prove it, can the tenant pay it? If the tenant is in bad financial condition and will be unable to defend against a simple nonpayment, why bother bringing a holdover with its long predicate notice period? In that case it might be best to do a nonpayment with its relatively short predicate notice period.

E. RESIDENTIAL VS. COMMERCIAL

A fundamental difference between commercial and residential landlord and tenant law is that in commercial landlord and tenant cases the concept of “freedom of contract” is given great deference by the courts, while residential landlord and tenant case law has developed restrictions to prevent a landlord from overreaching in its dealings with a tenant. For example, in the residential context, a reciprocal right to recover attorney’s fees is implied by law in favor of the tenant, even if not provided for in the lease . No such right exists in the commercial context.

Additionally, commercial tenancies often involve higher rents and revenues than residential tenancies. Residential landlord and tenant cases, however, can be far more emotionally heated because at stake is the threatened loss of an individual’s home. Moreover, tenants in residential cases are often pro se (i.e., un-represented).

For more chapters in these materials contact Michelle Maratto Itkowitz.