Co-Living – What it is. What it isn’t. How it’s good for tenants. How it’s good for landlords. And what its limits are.

December 20, 2017

On December 13, 2017, Michelle Itkowitz presented to the LandlordsNY 2017 Winter Property Management Symposium at New World Stages. Michelle’s topic this time was, “Co-Living Defined and Dissected – What it is. What it isn’t. How it’s good for tenants. How it’s good for landlords. And what its limits are.” Here is a link to the full materials. Here is an excerpt:

C. Co-Living Defined

I found that I needed a working definition of co-living for my practice, and this is what I came up with:

An arrangement by which a landlord rents an apartment to a group of tenants, for at least thirty days, where the tenants occupy and share the apartment as roommates, as an arrangement which the landlord consents to and facilitates as an active participant; the tenants have flexible terms, which are often short, and are allowed to vacate the apartment early without liability for the full term of the lease; if a roommate is lost, the landlord assists the remaining tenants with getting a qualified new roommate to take lost roommate’s place and gives the remaining tenants rent-relief while doing so; the landlord frequently provides the tenants with other advantages and amenities, including but not limited to furnishings and personal property, services, and thematic programming, such as dinners or lectures on topics of common interest to the roommates; co-living places a big emphasis on the creation of a community within the apartment; the price per square foot for the apartment is often higher than it would be if the same apartment was not rented for co-living. The advantages of co-living for the tenant are affordability, flexibility, convenience, limited liability for bad roommates, and community. The advantage of co-living to a landlord is a higher price per square foot and greater control of the occupants of an apartment.

II. WHAT CO-LIVING IS NOT

Next, let us go over in detail how co-living is an extremely different thing from other residential rental paradigms. Sometimes the best way to learn what something is, is to learn what it is not.

A. Co-Living is NOT the Classic Roommate Situation

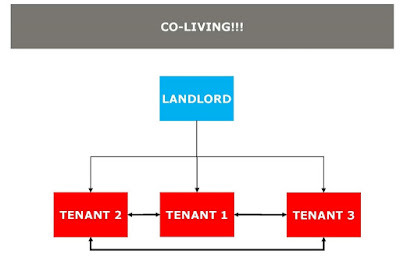

First, the below diagram shows the classic roommate situation:

Under this scenario, a tenant decides she wants an apartment that she probably cannot afford on her own. Therefore, she aggregates a group of roommates on Craig’s List or using social media. That tenant finds the apartment and becomes the contact person for the group of tenants with the landlord. Maybe the landlord puts only the contact tenant on the lease, or maybe all roommates are on the lease[fn1]. After the initial renting, the landlord is done.

If one of the roommates leaves or stops paying rent then there is tremendous pressure on the remaining roommates to make up the difference. When a landlord calls me up and tells me that one roommate has stopped paying rent, my best practices legal advice is always to sue ALL tenants on the lease, because they are all jointly and severally liable. This makes the nonpayment proceeding more expensive for the landlord, because there are more people to serve with the predicate notice and the nonpayment proceeding. This is a very stressful and burdensome situation for the tenants who paid their share of the rent. Now their names are in the Housing Court records even though they paid their share of the rent.

If there is only one tenant on the lease, this is all the more burdensome for that tenant. Also, consider the plight of the guarantor of the single tenant. I have often received calls from parents who guaranteed a lease for an adult child in New York City. That guarantor can find themselves pursued for tens of thousands of dollars.

None of this is ideal for the landlord, who just wants the rent, not a Housing Court proceeding or a Guarantor Action.

Furthermore, the classic roommate situation is fraught with other difficulties. If Tenant 1 bought the coffee maker and then leaves and takes it with him, gone is the coffee maker. Tenant-roommates in the classic scenario have to divide responsibility for buying items used by all, like toilet paper.

Moreover, the classic roommate situation does little in terms of creating community for people who are looking for that as part of a roommate experience.

B. Co-Living is NOT SRO Usage

Next, the below diagram shows a Single Room Occupancy use (“SRO use”):

In this scenario, a landlord goes out and rents rooms within an apartment directly to individual tenants, people who have nothing to do with one another, although they may share a bathroom and a kitchen. The landlord uses separate leases for each room and each tenant, with separate prices and terms. There are most likely locks on the outside of the individual bedroom doors, as if each bedroom door is the threshold to a separate living unit.

A landlord may not, however, rent rooms in regular apartments. Multiple Dwelling Law (“MDL”) § 4(16) states:

““Single room occupancy” is the occupancy by one or two persons of a single room, or of two or more rooms which are joined together, separated from all other rooms within an apartment in a multiple dwelling, so that the occupant or occupants thereof reside separately and independently of the other occupant or occupants of the same apartment.”

MDL § 301 says that every building will be used in conformity with its certificate of occupancy (“CO”). The CO will state whether a building contains apartments or whether it may be rented for SRO use. Therefore, MDL § 301 would be violated if an apartment in a regular building was rented for SRO use.

If MDL § 301 is violated, then, according to MDL § 302, the building’s mortgage goes into default, no rent is due from the tenants, no law suit for rent may be brought against the tenants, and:

“2. The department may cause to be vacated any dwelling or any part thereof which contains a nuisance as defined in section three hundred nine, or is occupied by more families or persons than permitted in this chapter, or is erected, altered or occupied contrary to law. Any such dwelling shall not again be occupied until it or its occupancy, as the case may be, has been made to conform to law.” [Emphasis supplied.][fn2]

The New York City Housing Maintenance Code (“HMC”) applies to all dwellings.[fn3] There is a similar definition of an SRO (to that in the MDL) in the HMC, which calls an SRO unit a “Rooming Unit” at § 27-2004(a)(15) and states:

“Rooming unit shall mean one or more living rooms arranged to be occupied as a unit separate from all other living rooms, and which does not have both lawful sanitary facilities and lawful cooking facilities for the exclusive use of the family residing in such unit. It may be located either within an apartment or within any class A or class B multiple dwelling.”

Under HMC § 27-2004(14), an “Apartment shall mean one or more living rooms, arranged to be occupied as a unit separate from all other rooms within a dwelling, with lawful sanitary facilities and a lawful kitchen or kitchenette for the exclusive use of the family residing in such unit.” Under HMC § 27-2004(4), a “family” is:

“(a) A single person occupying a dwelling unit and maintaining a common household with not more than two boarders, roomers or lodgers; or

(b) Two or more persons related by blood, adoption, legal guardianship, marriage or domestic partnership; occupying a dwelling unit and maintaining a common household with not more than two boarders, roomers or lodgers; or

(c) Not more than three unrelated persons occupying a dwelling unit and maintaining a common household; or….”

Here is an example of a recent Environmental Control Board case. The New York City Department of Buildings (“DOB”) issued violation notices to landlord for converting a two-family house to six SRO units [pursuant to Title 28 of the HMC which has to do with construction]. Landlord claimed that she hadn’t changed the building since buying it in 2014. She claimed that she lived on the first floor and landlord’s relatives lived on the second floor. But landlord submitted photographs showing that there were locks on room doors. DOB submitted a number of photographs documenting its claim. The Administrative Law Judge ruled against landlord and fined her $47,400, which included daily penalties. Landlord appealed and lost. Zhao: ECB App. No. 1700674 (8/3/17) [LVT Number: #27928].

C. Co-Living is NOT Short Term Leasing (Like Airbnb)

When a landlord puts her regular apartment building into use as a defacto hotel, on short-term leasing platforms, like Airbnb or VRBO, then the structure is much like the structure in the SRO diagram above, with all the same legal problems. If the terms for such renting are under 30 consecutive days, however, then there are additional legal problems.

The statutory prohibition against short-term occupancy is found in the New York State Multiple Dwelling Law (“MDL”), which applies to buildings with three or more units.

MDL § 4(8)(a), the relevant statute, states:

“A “class A” multiple dwelling is a multiple dwelling [3 units] that is occupied for permanent residence purposes…A class A multiple dwelling shall only be used for permanent residence purposes. For the purposes of this definition, “permanent residence purposes” shall consist of occupancy of a dwelling unit by the same natural person or family for thirty consecutive days or more and a person or family so occupying a dwelling unit shall be referred to herein as the permanent occupants of such dwelling unit. The following uses of a dwelling unit by the permanent occupants thereof shall not be deemed to be inconsistent with the occupancy of such dwelling unit for permanent residence purposes:

(1)(A) occupancy of such dwelling unit for fewer than thirty consecutive days by other natural persons living within the household of the permanent occupant such as house guests or lawful boarders, roomers or lodgers; or (B) incidental and occasional occupancy of such dwelling unit for fewer than thirty consecutive days by other natural persons when the permanent occupants are temporarily absent for personal reasons such as vacation or medical treatment, provided that there is no monetary compensation paid to the permanent occupants for such occupancy.” [Emphasis supplied.]

At this point, when a landlord calls me about an Airbnb problem in her or his building, my first question is this – am I dealing with real human beings attempting to engage in the “sharing economy” or am I dealing with a de facto hotelier, a “professional operator” – someone who rents a whole bunch of apartments, which he or she never lives in, and which he or she continuously illegally short-term sublets.

According to the office of the New York State Attorney General, Eric T. Schneiderman, almost half of Airbnb’s $1.45 million in 2010 revenue in the city came from hosts who had at least three listings on the site.[fn4] An analysis of global Airbnb listings in 2014 showed that hosts offering multiple listings made up over 40% of the company’s business.[fn5] A 2016 report from Penn State researchers for the American Hotel and Lodging Association determined that $378M of Airbnb’s total revenue—nearly 30%—was generated from “full-time operators” listing rentals year-round.[fn6]

Dealing with a professional operator is completely different from dealing with a regular person. I had a client recently who discovered that one of his tenants, let’s call him “John”, had rented three apartments in the building, using his wife’s name for one unit and his friend’s name for another. John did not live in any of the three units and all three were continuously rented on Airbnb. The landlord was furious. When he confronted John, John said, “When the Marshal comes, I will stop. I have a lawyer and have been in this situation before.” The landlord then made a terrible mistake – (without consulting a lawyer) he hired a security guard to prevent guests of the three units from entering. John took the landlord immediately to court on three illegal lockout proceedings and won. Landlord had to stop blocking access and begin legitimate court cases. You can never use self-help eviction against a residential tenant in New York City. You can NOT lock a tenant out of their apartment. In New York State, in the context of a residential lease, a landlord is forbidden from resorting to self-help under any circumstances and can be subject to compensatory, punitive, and treble damages.[fn7]

Suffice it to say, a professional Airbnb operator is NOT engaged in co-living, even if the pro-operator tries to dress it up that way.

D. Co-Living is NOT Micro Units

This last section has no law in it, and it contains mostly my opinion, so skip it if you want to.

Co-living is NOT Micro! Micro units, to me, mean that a development has little tiny apartments. Those apartments are not rooms, they have kitchens and baths. To compensate for the tiny apartments, the development will have great building-wide common space amenities. Maybe your kitchen is teeny-tiny, but there is a great barbeque area on the room, complete with tools and stocked with charcoal. Maybe you have almost no living room, but there are party rooms in the building you can rent, and various decks and lounges available for free. This is all great. But it is not co-living. Micro means you have a small apartment in a great building.

Co-Living has an unmistakable communal aspect to it that the Micro development lacks.

[fn1] There are pros and cons to each approach; See the LNY online lease!

[fn2] In Association For Neighborhood Rehabilitation, Inc. v. Board of Assessors of Ogdensburg, 81 A.D.3d 1214 (3rd dept. 2011), the court found that “SRO tenants have a single sleeping room, with access to a communal kitchen, bathroom and social area.”

[fn3] N.Y. ADC. LAW § 27-2003.

[fn4] http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/30/magazine/the-business-tycoons-of-airbnb.html?mwrsm=Email&_r=0.

[fn5] https://www.fastcompany.com/3043468/the-secrets-of-airbnb-superhosts.

[fn6] https://www.bisnow.com/national/news/hotel/report-professional-operators-make-a-killing-off-airbnb-59859.

[fn7] See Real Property Actions and Proceedings Law (“RPAPL”) § 853; Romanello v. Hirschfeld, 63 N.Y.2d 613, 615 (1984).

[END OF EXCERPT]