December 21, 2019: UPDATE ALERT! Seven months after the Redbridge decision the status quo has been restored, by the New York State legislature enacting Real property Law § 235-h stating that: “no commercial lease shall contain any provision waiving or prohibiting the right of any tenant to bring a declaratory judgment action with respect to any provision, term or condition of such commercial lease.”

More later!

On May 21, 2019, Michelle Itkowitz taught a Continuing Legal Education class for The York Group, LLC, with the National Law Institute, hosted by Morgan Stanley, entitled Goodbye Yellow Brick Road…and Goodbye Yellowstone Injunction? The Implications of 159 MP Corp.v Redbridge Bedford, LLC for commercial tenants and landlords.

Below is a copy of the materials presented.

I. WHAT A YELLOWSTONE INJUNCTION IS AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO COMMERCIAL TENANTS AND LANDLORDS

A. Types of Defaults Subject to Conditional Limitations in a Lease

One of the landlord’s most powerful remedies, a default subject to a conditional limitation pursuant to the lease, permits the landlord to terminate the lease by following certain procedures.

1. Non-Rent Defaults Subject to Conditional Limitations

The following are events of default subject to a conditional limitation under the Real Estate Board of New York, Inc.’s Standard Form of Store Lease (“the REBNY Lease”):

“If the Tenant defaults in fulfilling any of the covenants of this lease other than the covenants for the payment of rent or additional rent; or if the demised premises becomes vacant or deserted; or if any execution or attachment shall be issued against Tenant or any of Tenant’s property whereupon the demised premises shall be taken or occupied by someone other than Tenant; or if the lease be rejected under Section 365 of Title II of the U.S. Code (Bankruptcy Code); or if Tenant shall have failed, after five (5) days written notice, to redeposit with Owner any portion of the security deposit hereunder which Owner has applied to the payment of any rent and additional rent due and payable hereunder; or if Tenant shall be in default with respect to any other lease between Owner and Tenant; or if Tenant shall fail to move into or take possession of the premises within thirty (30) days after the commencement of the term of this lease….”

Other defaults which may be included in the lease as subject to a conditional limitation are:

- assigning, mortgaging or encumbering the lease or subletting without the landlord’s permission

- the filing of a mechanic’s lien against the premises which is not discharged within a period of time after notification of the tenant by the landlord

- the failure to maintain insurance

- assigning the lease, or any interest in the lease, transfer ownership of the lease

- illegal sublets

- closing for a period of ten or more days not for landlord authorized renovations

2. Nonpayment of Rent as a Conditional Limitation

Although the many leases specifically exclude such, a lease can provide a mechanism whereby landlord may terminate the lease, after default in the payment of rent, in the commercial context. Properly drafted, a conditional limitation clause for the nonpayment of rent in a commercial lease will be enforced by the courts and is, perhaps, the landlord’s most powerful remedy, nonpayment being the most common default. This is particularly true where the market has quickly improved and the lease-rent has fallen “below market”. A properly structured conditional limitation for the non-payment of rent should utilize the language cited approvingly by the court in Grand Liberte Co-op Inc. v. Billhaud, 126 Misc.2d 961 (1stDept. App. Term. 1984), expressly making the conditional limitation applicable to rent defaults and stating that “it [is] the intention of the parties hereto to create hereby a conditional limitation”. Note, however, that this strategy will not work in a residential context. A conditional limitation regarding the nonpayment of rent in a residential lease has been held to violate public policy as it would provoke a forfeiture, and the law disfavors automatic forfeitures of residential tenancies. Semans Family Ltd. Partnership v. Kennedy, 177 Misc.2d 345 (N.Y.C. Civ.Ct. N.Y. Cty. 1998).

B. Notice to Cure

In most commercial leases, the landlord must first notify the tenant of the default and set forth a time period in which the tenant must cure the default; or, if it is impossible to cure within the time period, it must set forth a time period in which the tenant must begin curing the default. This notice is commonly referred to as a “notice to cure default”.

C. “Yellowstone” and Tolling Time to Cure Defaults

Giving a notice to cure may prompt the commercial tenant to initiate a proceeding in Supreme Court commonly referred to as a “Yellowstone”, so called after the case of First National Stores v. Yellowstone Shopping Center, 21 N.Y.2d 630 (1968), rearg. denied, 22 N.Y.2d 827 (1968).

The essence of a Yellowstone is a declaratory judgment complaint accompanied by an emergency stay application (which is routinely granted, at least in the form of a temporary restraining order, pending a hearing on a preliminary injunction), which seeks a trial on the issue of whether the tenant is indeed in violation of the lease. This procedure is designed to toll the time the tenant would ordinarily have to cure a lease violation while the court resolves the issue of whether the tenant is indeed in violation and/or has cured the violation. If the court finds the tenant in violation, then by virtue of the stay of the notice to cure, the tenant still has the opportunity to cure the violation before the cure period ends. This process can buy the tenant significant time as the resolution of the proceeding can take months or years.

The purpose of a Yellowstone injunction is to maintain the status quo by means of a temporary stay while the tenant challenges the landlord’s notice to cure. See e.g., Jemaltown of 125th Street, Inc. v. Leon Betesh/Park Seen Realty Assocs., 115 A.D.2d 381 (1st Dept. 1985); Fratto v. Red Barn Farmers Market Corp., 144 A.D.2d 635 (2nd Dept. 1988).Thus, the injunction tolls the cure period set forth in the landlord’s notice of default until there is a judicial determination of the parties’ rights. See, Finley v. Park Ten Associates, 83 A.D.2d 537 (1st Dept. 1981); South Ferry Building Co. v. J. Henry Schroder Bank & Trust Co., 91 A.D.2d 963 (1st Dept. 1983).

To demonstrate one’s entitlement to a Yellowstone injunction, a tenant must demonstrate that he/she: (i) holds a valuable commercial lease (ii) has received a notice to cure; (iii) has requested injunctive relief prior to the termination of the lease; and (iv) is prepared and maintains the ability to cure the alleged default by any means short of vacating the premises. Garland v. Titan West Assocs., 147 A.D.2d 304 (1st Dept. 1989). “These standards reflect and reinforce the limited purpose of a Yellowstone injunction: to stop the running of the applicable cure period.” Graubard Mollen Horowitz Pomeranz & Shapiro v. 600 Third Avenue Associates, 93 N.Y.2d 508 (1999).

A Yellowstone injunction can provide a modicum of protection to landlords as well as tenants, because such injunctions are often conditioned upon the tenant’s ongoing payment of rent and/or the posting of a bond to protect the landlord from a wrongfully issued injunction.

The First Department has held that commercial tenants have a right to a virtually automatic issuance of a Yellowstone injunction and has held that in order to obtain a Yellowstone, rather than requiring the tenant to prove on his application that he can cure the alleged default, a tenant must merely state his desire and ability to cure the default by any means short of vacating the premises. See Herzfeld & Stern v. Ironwood Realty Corp., 102 A.D.2d 737 (1st Dept. 1984); 34 N.Y.Jur.2d § 261 (“where a tenant denies any default and demonstrates that the landlord has given notice of default, and where a period of time remains within which to cure, the tenant is entitled to a grant of preliminary relief in the form of a Yellowstone injunction; since the law does not favor forfeitures, the tenant is not required, as a prerequisite to such relief, to demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits or an ability to cure, and the proper inquiry instead is whether a basis exists for believing that the tenant desires to cure and has the ability to do so through any means short of vacating the premises”). Furthermore, a tenant is entitled to a Yellowstone injunction when the tenant argues that he is not in violation of the lease, and that if he is, he agrees to cure any such violations. See Empire State Building Assocs. v. Trump Empire State Partners, 245 A.D.2d 225 (1st Dept. 1997) (where a tenant can show that it is able and willing to bring itself into compliance with the lease absent vacating the premises, forfeiture is inappropriate).

If the tenant is successful in having the Yellowstone injunction implemented, then the landlord must answer the Supreme Court action and counterclaim for termination of the tenancy.

D. Termination Notice

If no Yellowstone proceeding is commenced and the default is not cured or being cured by the date specified in the notice to cure or if the tenant refuses to cure (see below), then the landlord may notify the tenant that the lease will be terminated in a certain number of days, as per the lease. This notice is commonly referred to as a “notice of termination”. Notices to cure and notices of termination pursuant to the terms of a lease are served on the tenant in accordance with the lease. No statute specifies other methods of service for notices given strictly pursuant to a lease. See Rose Assoc. v. Bernstein, 138 Misc.2d 1044 (N.Y.C. Civ.Ct. N.Y. Cty. 1988). If the lease is silent on a method of service, the method used must be “reasonable”.

After the expiration of the notice of termination, the landlord may commence a summary holdover proceeding against the tenant to recover possession of the premises (see more about summary proceedings below). In such event, the tenant can still argue there is no default or that the notices are defective. If tenant prevails, there is no harm to the tenancy. If the tenant does not prevail, the proceeding may well end with the eviction of the tenant.

E. Defaults the Tenant Refuses to Cure

If a tenant’s position is that it refuses to cure the default, Tenant can’t have the Yellowstone. In Linmont Realty, Inc. v. Vitocarl, Inc., 147 A.D.2d 618 (2nd Dept. 1989), the Yellowstone application was denied. There were 17 defaults, including failure to renew environmental liability insurance, failure to keep daily records of gasoline inventory, failure to have tanks tested, failure to permit the defendants to inspect records of tank tests and inventory control, failure to clean and maintain the premises, and illegally subletting a portion of the premises for the storage and distribution of newspapers. The Linmont court reasoned:

“To procure a Yellowstone injunction, a commercial tenant must demonstrate, inter alia, that it has the desire and ability to cure the alleged default by any means short of vacating the premises. The plaintiff herein has made no offer to cure any of the charged defaults, alleging instead that many of the alleged defaults listed in the Notice of Termination of Lease were not its responsibility, that various conditions did not exist as claimed by the defendants, and that the remainder of the defaults had been waived by the defendants acceptance of rent with knowledge of their existence. [(internal quotation marks and citation omitted)].”

F. Why Being in Supreme Court on a Yellowstone Case is Different Than Being In a Summary Proceeding in Civil Court

In most instances when a landlord finds it necessary to sue a commercial tenant to recover rent or possession of a premises, the proper vehicle is a summary proceeding for the recovery of real property. A summary proceeding for the recovery of real property (“summary proceeding”) is an expedited lawsuit, for the recovery of rent and possession of a premises, created by the New York State Legislature in 1820 and governed by Article 4 of the Civil Practice Law and Rules (“CPLR”) and Article 7 of the Real Property Actions and Proceedings Law (“RPAPL”). Summary proceedings are expeditious because the parties’ procedural rights and remedies are severely limited. Among other things, for example, the tenant’s time to answer the lawsuit is accelerated and, absent leave of court, there is no discovery. NYU v. Farkas, 121 Misc.2d 643 (N.Y. Civ. Ct. 1983) (defines “ample need” test for discovery to be allowed in a summary proceeding).

Therefore, if there is not a successful Yellowstone application by a commercial tenant, then the case will, generally, go faster for the landlord and cost less for the landlord to prosecute. It should be noted that whether a case is litigated in Supreme Court, pursuant to a Yellowstone application and replete with discovery, or whether a case is litigated more swiftly in New York City Civil Court, via a summary proceeding – the merits are still the merits.

II. HOW THE REDBRIDGE CASE ALLOWS THE PARTIES TO WAIVE TENANT’S RIGHT TO SEEK A YELLOWSTONE INJUNCTION

A. Redbridge Holding

On May 7, 2019, 159 MP Corp. v. Redbridge Bedford LLC, 2019 WL 19955262019 N.Y. Slip Op. 03526, was decided by the New York State Court of Appeals. It was a 4-3 decision written by Chief Judge DiFiore, with a long dissent by Judge Wilson.

The commercial leases in Redbridge were for 22-years, for 13,000 square feet space, and utilized a standard form with a 36-paragraph rider. The tenant was a Foodtown. Rents started at $341k per year and were to go up to $564k per year. I peeked at the Second Department case, 159 MP Corp. v. Redbridge Bedford LLC, 160 A.D.3d 176 (2nd Dept. 2018), for more details, and it appears that the lease began in 2010, and it was only four years into the 20+-year term when the landlord attempted to terminate. The alleged breaches, “included the failure to obtain various permits, the arrangement of the premises in a manner that created fire hazards, the existence of nuisances and noises, and the failure to allow for sprinkler system inspections…”.

Redbridge holds that:

“In New York, agreements negotiated at arm’s length by sophisticated, counseled parties are generally enforced according to their plain language pursuant to our strong public policy favoring freedom of contract. In this case, commercial tenants who unambiguously agreed to waive the right to commence a declaratory judgment action as to the terms of their leases ask us to invalidate that waiver on the rationale that the waiver is void as against public policy. We agree with the courts below that, under the circumstances of this case, the waiver clause is enforceable, requiring dismissal of the complaint.”

B. The Specific Lease Language Upheld

The specific lease language upheld as enforceable by the Court of Appeals in Redbridge was this:

“Tenant waives its right to bring a declaratory judgment action with respect to any provision of this Lease or with respect to any notice sent pursuant to the provisions of this Lease . . . [I]t is the intention of the parties hereto that their disputes be adjudicated via summary proceedings.”

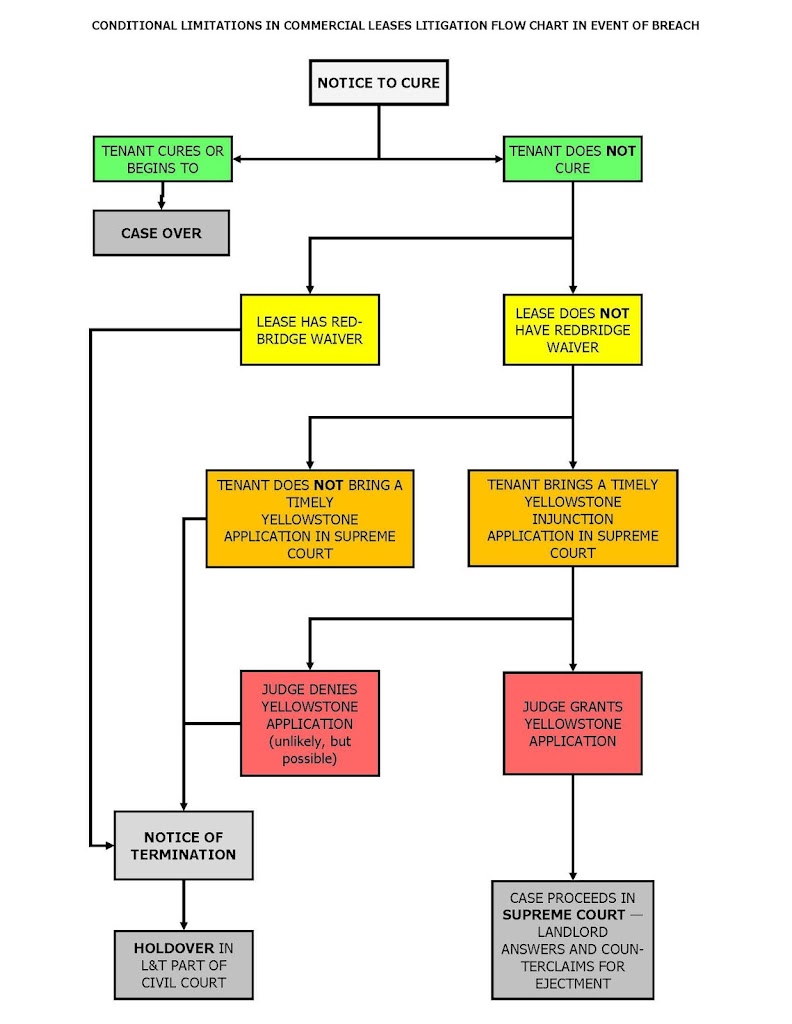

III. THE NEW WAY THINGS WILL WORK FOR COMMERCIAL LANDLORD AND TENANT LITIGATORS – A CHART!

It would not be a CLE without a flowchart now would it!

IV. SOME GUESSES ABOUT THE REAL-LIFE IMPLICATIONS OF REDBRIDGE – I.E. YELLOWSTONE INJUNCTIONS ARE ALIVE AND WELL AND PROBABLY WILL BE FOR A WHILE.

Yellowstone injunctions are alive and well and probably will be for a while.

A. Many current leases will not contain the Redbridge waiver language.

Many current leases will not contain the Redbridge waiver language.

I looked at the last three commercial landlord and tenant litigations that I worked on. Those concerned the following types of commercial leases:

- A net lease for an entire building in Brooklyn,

- A lease for a small office suite in a class B building in Manhattan,

- A lease for a store in a shopping plaza in Queens,

– AND NONE OF THEM HAD REDBRIDGE WAIVER CLAUSES!!!

B. The profession is slow to respond, so there will be a lag time before landlord-drafters are including the Redbridge waiver.

The profession is slow to respond, so there will be a lag time before landlord-drafters are including the Redbridge waiver in commercial leases.

C. When landlord-drafters attempt to include the Redbridge waiver, some tenant-drafters will successfully resist.

When landlord-drafters attempt to include the Redbridge waiver in commercial leases, some tenant-drafters will successfully resist. It will depend on whose market it is and how much bargaining power the tenant in question has.

Who knows what interesting new clauses will be negotiated? Perhaps a tenant-drafter will allow a Redbridge waiver in if the deadlines for curing a default are extended from 15 days to 45 or 60 days.

D. Again, the profession is slow to respond, so there will be a lag time before litigators working for landlords in commercial tenant default matters know to look for Redbridge waiver language.

Again, the profession is slow to respond, so there will be a lag time before litigators working for landlords in commercial tenant default matters know to look for Redbridge waiver language. If landlord’s counsel does not know to look for the Redbridge waiver, then she will not raise it and thwart a Yellowstone injunction.

E. Inevitably, there will be disputes about whether lease language, which is not the specific language dealt with by the Court of Appeals in Redbridge, gives rise to the same waiver.

Inevitably, there will be disputes about whether lease language, which is not the specific language dealt with by the Court of Appeals in Redbridge, gives rise to the same waiver. That should be fun.

F. Ultimately, as Redbridge does reduce the number of Yellowstone applications, these cases will be hashed out more frequently in the commercial landlord and tenant part of the NYC Civil Court and the world will continue to spin on its axis.

Ultimately, as Redbridge does reduce the number of Yellowstone applications, these cases will be hashed out more frequently in the commercial landlord and tenant part of the NYC Civil Court.

The world will continue to spin on its axis.