Remedies for Commercial Tenant Monetary Defaults

July 31, 2023

Michelle Itkowitz contributes chapters to the New York State Bar Association’s two-volume Commercial Leasing treatise. The Fourth Edition is due out shortly. One of Michelle’s chapters is entitled “Commercial Lease Remedies Analysis”. Below, is an except from that chapter.

FAILURE TO PAY RENT OR ADDITIONAL RENT

In the event of a monetary default by tenant, landlord typically has many possible remedies to choose from. Some of these remedies are not mutually exclusive and can be used in combination with one another.

A. Nonpayment Proceedings

As discussed above in the section on summary proceedings, a Nonpayment is a lawsuit seeking the recovery of rent due and, in the absence of full and timely recovery of rent due, possession of the premises. RPAPL § 711(2).

A rent demand on at least fourteen (14) days’ notice is a required predicate for a Nonpayment. RPAPL § 711(2). A rent demand must state that tenant has the alternative of paying the arrears or surrendering the premises. J.D. Realty Associates v. Jorrin, 166 Misc.2d 175 [New York City Civil Court 1995]. Rent demands must be served upon a tenant by a process server. RPAPL § 735.

B. Draw Down of Security Deposit or Letter of Credit

Before initiating legal action, almost every commercial lease will allow landlord to draw down on the security deposit or letter of credit (hereinafter, collectively “security”).

This is an aggressive move that the author never recommends to her landlord clients, unless a tenant is already out of the subject premises. Why? Because once the security is drawn down on, it is not always a certainty that tenant can replace it, especially if it is in the form of a letter of credit, which requires a banking relationship. Also, by curing tenant’s nonpayment default, via the drawdown, landlord then loses the ability to avail itself quickly of the nonpayment proceeding option we discussed above.

Furthermore, Landlord might, after the drawdown, demand that tenant replenish the security. Almost all commercial leases require replenishment. If tenant does not replenish the security, then tenant is in a non-monetary default of the lease (see the non-monetary default section above). In that case, landlord can give tenant a Notice to Cure Default, and failing such cure, landlord could then terminate the lease. Once the Notice to Cure Default is served, however, as discussed extensively above, that matter is then vulnerable to a Yellowstone Injunction.

C. Termination of the Lease for the Nonpayment of Rent

Speaking of Yellowstone Injunctions, here in this rent default section of our chapter, let us now consider the fact that some commercial leases (the author estimates about half in New York) include the nonpayment of rent as an event of conditional limitation.

Properly drafted, a conditional limitation clause for the nonpayment of rent in a commercial lease will be enforced by the courts. A properly structured conditional limitation for the non-payment of rent should utilize the language cited approvingly by the court in Grand Liberte Co-op Inc. v. Billhaud (Grand Liberte Co-op Inc. v. Billhaud, 126 Misc.2d 961 [App Term 1st Dept 1984] (Holding that a conditional limitation for the nonpayment of rent is valid where it is expressly made and stating that “it [is] the intention of the parties hereto to create hereby a conditional limitation.”) (Note, however, that this strategy will not work in a residential context. A conditional limitation regarding the nonpayment of rent in a residential lease has been held to violate public policy as it would provoke a forfeiture, and the law disfavors automatic forfeitures of residential tenancies. Semans Family Ltd. Partnership v. Kennedy, 177 Misc.2d 345 [New York City Civil Court, New York County 1998].)

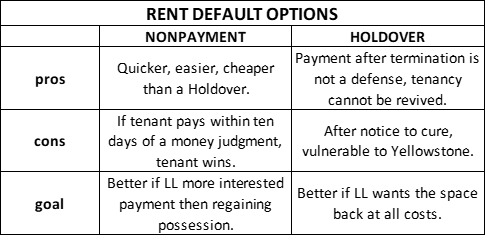

If tenant owes landlord significant rent, is it better to do: (a) a Rent Demand, followed by a Nonpayment; or a Notice to Cure Default, then a Notice of Termination, followed by a Holdover? That depends. Here is a chart:

D. Acceleration Clauses

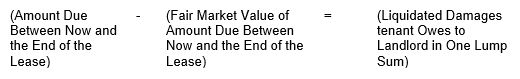

Normally landlord will sue tenant for all the rent tenant owes through the date of a trial. Then, if the lease term is still running and nobody else rents the space, tenant owes landlord more money and landlord is forced to sue tenant all over again. As a practical matter, this seldom happens for two reasons, either: (a) the case settles and that ends tenant’s continuing liability; or (b) tenant is judgment-proof and landlord has no incentive to sue tenant further. Nevertheless, to deal with this issue, many commercial leases contain a seldom-used clause, what the author calls a “fair-market acceleration clause”. It is a formula that works as follows:

The Pandemic was the first time the author used (or saw anyone else try to use) these clauses. These clauses are somewhat useful exactly because so many leases were under market after the Pandemic.

Example: Tenant’s rent is currently $38,754.28. If the fair market value is $20k per month, the delta is $18k a month. There are 27 months left on the lease. Theoretically landlord could sue tenant all at once for a number in the vicinity of $486,000 (27 x $18k).

E. Clawing Back Free Rent

Some leases provide for tenant to have a period of free rent after the commencement date of the lease. Some leases also provide specific remedies for claw back of the free rent in the event of tenant’s monetary default. Here is an interesting example from the author’s files:

Anything contained hereinabove to the contrary notwithstanding, if Tenant at any time during the Term of this Lease breaches any material covenant or condition or provision of this Lease and fails to cure such breach within any applicable grace period, and provided this Lease is terminated by Landlord because of such material default then, in addition to all other damages and remedies herein provided and to which Landlord may otherwise be entitled, Landlord shall also be entitled to the repayment of a proportionate share of the Free Rent, equal to the Free Rent multiplied a fraction, the numerator of which is of whole months from the date of such termination to the date when the Term would have otherwise expired and the denominator of which is 186, which repayment Tenant shall make upon demand therefor.

Notice that the above sections do not, however, explain how (by what amount or percentage) the free rent is reduced! More often, one sees commercial leases that allow some specific mechanism for the claw back of free rent received at the beginning of the tenancy. Frequently, these claw back mechanisms will be time sensitive. The further into the lease term you go, the less free rent can be clawed back.

One might strategically ask – if tenant is already having trouble paying the rent, what good does it really do landlord to heap on more arrears by clawing back free rent? That is a good question. An answer might be as follows. Threatening to pull the claw back trigger is useful if the tenancy is young and landlord wants to emphasize to tenant that paying monthly rent on time is not optional, and that there could be many consequences associated with not paying in full and on time. On the other hand, if the tenancy fails and tenant vacates early, why not tack this extra liability onto the money judgment.

F. Looking to the Franchisor

Some tenants are franchisees of bigger companies. In such cases, the franchisor will usually play some role in the commercial lease. For example, sometimes there will be addendum to the lease regarding the franchise aspects of the relationship, which states that franchisor has a security interest in the lease and all the contents of the premises. In such cases, the lease will require any notice sent to tenant to also be sent to franchisor in a certain manner and at a certain address. Such requirements should be honored by landlord. You never know, franchisor may sweep in and cure the default and it might even assume the lease. The franchisor might make a much better tenant than tenant.

G. Suing the Good Guy Guarantor

See Chapter 35 for all you could ever hope to learn on enforcing Good Guy Guaranties!

H. Prejudgment Interest

If landlord obtains a money judgment against tenant, pre-judgment interest, back to the date of the first arrears (CPLR § 5001), could be assessed on the judgment at Nine Percent (9%) per annum (CPLR § 5004).

I. Legal Fees

Most commercial leases contain legal fee clauses. Most typically, a commercial lease allows landlord to recoup its reasonable legal fees from tenant in the event that landlord prevails in a lawsuit between the parties. Occasionally, however, a commercial lease will contain a legal fee clause that calls for the prevailing party (be it landlord or tenant) to recoup legal fees against the other in litigation between the parties. In either case, such fees can significantly increase the liability of the party charges with them. Here is a sample legal fee clause from the most recent lease the author litigated:

The losing party shall reimburse the prevailing party for all attorneys’ fees for any legal action commenced against the other. If the Tenant pays its rent arrears after the commencement of any action and the action is disposed of Tenant shall still be liable for the legal fees. Such amounts shall be paid on demand.